Macao to Havana and Beyond: The Chinese-Cuban Coolie Trade - Indentured Labor (or Pseudo-Slavery) from 1847-1874

Posted by Jessica Katz on

Macao to Havana and Beyond: The Chinese-Cuban Coolie Trade - Indentured Labor (or Pseudo-Slavery) from 1847-1874

By Jessica Katz, MScN

Table of Contents

- BACKGROUND

- CHINESE COOLIE TRADE: SUMMARY

- WHAT

- What is a “coolie”?

- Coolies vs African Slaves

- What Did the World Do About the Coolie Trade?

- WHO

- The Coolies

- The Crimps

- The Cubans

- WHERE

- Destination Countries

- China

- Transport

- On Arrival

- Life and Work

- WHEN

- WHY

- Why Trade in Coolies?

- HOW

- How Were Coolies Recruited

- How Did Coolies Experience Ship Life?

- How Did Coolies Respond to Their Indentured Labor Experiences?

- How Did the Coolie Trade End?

- References

BACKGROUND

In 2022, Katz Fine Manuscripts, Inc. was fortunate to establish a relationship with a collector who has focused his collecting journey on 19th century Chinese-Cuban content, acquiring treasures directly from academic sources in Cuba. Our initial acquisition included 29 ship manifests which had been stored in Havana, from the Chinese coolie indentured labor trade of 1847-1874. These manifests connect the collector and researcher to intimate details of a moment in world history whereby colonizing countries manipulated and forced Chinese men into indentured labor to boost the performance of their colonies’ plantations, while simultaneously taking a “virtuous” stand against African slavery.

Over time, we have branched out from the manifests, cultivating a thriving Chinese-Cuban manuscript collection. We have a sensational selection on offer in our online store. As we built our collection we gained a deep personal and academic understanding of the circumstances surrounding the coolie trade, which paralleled or succeeded African slavery, depending on the colony. We hope that this article helps to familiarize you with the coolie trade, whether you are a collector, researcher, or student looking for sources for your paper. To view our Chinese-Cuban collection, click here, or follow links throughout the write-up below.

[Students: e-mail us if you need help referencing our blog in your paper! We are happy to help you out].

CHINESE COOLIE TRADE: SUMMARY

The Chinese coolie trade, a system of indentured labor that targeted young, poor Chinese men, operated from 1847-1874. Throughout this period, African slavery was slowly being abolished around the world. The coolie trade was initiated by Britain and was eventually dominated by both Britain and the United States of America. Chinese coolie laborers were sent to work in British, American and Spanish colonies, and the nature of the trade changed throughout its 27-year operation, due to social and political pressures. The coolie trade took place, in large part, between the shipping port in Macao (now a part of China, then under Portuguese rule) and Havana, Cuba (then under Spanish control). This article will explore the WHAT, WHO, WHERE, WHEN, WHY and HOW of the coolie trade in general with a special focus on Macao-Havana trade.

WHAT

What is a coolie?

What similarities and differences existed between the Chinese coolie trade and the African slave trade?

What was done about the coolie trade?

What is a “coolie”?

The term coolie was used to describe laborers deemed to be low class by Eastern countries (Holden, 1864). The Chinese coolie trade (sometimes called la trataamarilla [the yellow trade]) was a system in which Chinese men were indentured (contracted) through questionable means, and shipped overseas to countries requiring low-cost labor (Hu-Dehart, 1993). The coolies were forced or coerced into signing labor contracts, which were then sold to plantation owners in places like Peru and Cuba for somewhere between $300 and $1,000 American dollars (Holden, 1864; Farley, 1968). The plantation owner who bought a coolie’s contract became their defacto master.

Coolies vs African Slaves

“[The coolie trade] was erected upon the foundations laid by [African] slavery. As with slaves the planters enjoyed 'absolute power' over the coolies” (Hu-Dehart, 1993, p.76).

The coolie trade and African Slave Trade were similar in that people were transported from their country of origin to a location where they would be made to work. Poor Chinese men were coerced or forced onto coolie ships, many of which had previously been used as African slave ships (Yun & Laremont, 2001).

What differentiated the coolie trade from African slavery (which was slowly being phased out in many parts of the world as coolies were phased in - more on that later) was that coolies signed contracts. The contracts themselves, however, were extremely problematic. Men who were recruited or forced to become coolies often could not read and had low levels of education. Their understanding of the contracts they were signing was questionable. There was no government oversight, so coolies had no recourse if their contract was dishonored or they were mistreated (Yun & Laremont, 2001).

What Did the World Do About the Coolie Trade?

The world was aware of the coolie trade. It occurred in plain sight, at the same time that social and political pressure in Britain and the United States was propelling the end of the African Slave Trade. For some colonies, coolies were a way to acquire cheap labor without the stigma of slave ownership. While the negatives of the coolie trade were, at times, reported in the media, there was no substantive action taken to permanently stop the coolie trade.

An 1864 American Harper’s New Magazine article titled A Chapter on the Coolie Trade (Holden, 1864) stated, “...an old form of slavery has been instituted under a new name and many a deluded Coolie is to-day under a more hopeless and terrible bondage than the African from Gabook” (p. 1). The coolie trade would continue for a decade after this article was published. There were moves made by various governments [link to WHEN section] to slow or stop the coolie trade in response to shifting political pressure, but It was not abolished until China stepped in and put an end to it in 1874 (Gines-Blase, 2021).

WHO

Who were the coolies?

Who were crimps?

Who managed the Macao-Havana coolie trade?

The Coolies

Coolies were usually men under the age of 30 who were poor and living in China’s Guangdong province (Farley, 1968; Hu-Dehart, 1993; Laremont & Yun, 2001). These men were promised ‘free’ emigration out of China in exchange for signing a seemingly simple contract…which they largely could not read or understand (Farley, 1968). In some cases, these Chinese men were not invited to sign contracts and were instead tricked or taken by force. The Chinese men who became Coolies were not protected by any government-imposed laws or programs, either in China or in the receiving countries where they would be taken to work (Holden, 1864). Once they either agreed or were forced to sign a contract, they were put on boats and sent on months-long journeys to a country or colony that required long-term, inexpensive laborers. The Coolies spent their time playing music, gambling with dominoes, fighting, and eating their tiny rations of boiled rice and salt fish (Holden, 1864). Sadly, many men, upon realizing their fate, either attempted suicide or began violent uprisings aboard the ship in pursuit of freedom.

The Crimps

Most Coolies were either recruited through deception or force by fellow Chinese men acting as labor agents and referred to as “crimps” (Hu-Dehart, 1993, p. 75). Crimps were contracted by colonial Coolie traders to supply young Chinese men to be shipped overseas and labor in a variety of countries, including Cuba. Farley (1968) describes one tactic used by crimps to acquire a new laborer:

“A woman with a child would pass two men. The child would drop its bonnet and the two men would pick it up and hand the bonnet to the mother. As a “reward” the woman gave the two men drugged cakes, the men passed out and were dragged aboard a coolie ship” (p. 266).

The Cubans

Between 1847-1874, between 125,000 and 150,000 Chinese indentured or contract laborers, almost all male, were sent to Cuba (Hu-Dehart, 1993, p. 67; Yun & Laremont, 2001). The major player in starting up the Chinese coolie trade in Cuba, where coolies were needed to grow Cuban sugar production on plantations, was a company called Real Junta de Fomento y Colonización (Yun & Laremont, 2001). Real Juanita partnered with the company Julieta y Cia in London, England, which was run by cousins Julián Zulueta [0012023] and Pedro Zulueta (Yun & Laremont, 2001). Together, these companies schemed to transport Chinese men to Cuba and sell the men. More specifically, they sold each man’s contract, as opposed to the man himself, to Cuban plantation owners. They relied on Pedro Zulueta’s experience as a successful African slave trader to help them create efficient processes. The Zulueta cousins found labor agents in Asia (Fernando Aguirre in Manila and a Mr. Tait based in Amoy/Xiamen) and contracted their companies to get the first shipment of coolies from China to Havana, Cuba (Yun & Laremont, 2001).

WHERE

Where did the coolie trade occur?

Where did the coolies stay during their transport?

Where were the coolies taken on arrival?

Where did the coolies live and work?

Destination Countries

According to Yun & Laremont (2001), “coolie labor was utilized in Cuba, Peru, Guyana, Trinidad, Jamaica, Panama, Mexico, Brazil, and Costa Rica, among other places in the Americas.” (p. 101). There was also demand for coolie labor in Chile, the West Indies, California and Australia (Farley, 1968).

Some of these locations used coolie labor to replace slave labor. The British colonies, such as Jamaica and Trinidad engaged in the coolie trade after slavery had officially ended (Yun & Laremont, 2001). Peru also abolished slavery at the time the coolies were introduced (Hu-Dehart, 1993). In Peru, coolies initially worked under free Black men, and eventually became the primary laborers (Hu-Dehart, 1993).

Conditions in Peru were deplorable for coolies, with 80,000 to 100,000 coolies being brought to Peru to work in their mines, haciendas, plantations, factories, and more, and only one-third surviving their service term (Farley, 1968).

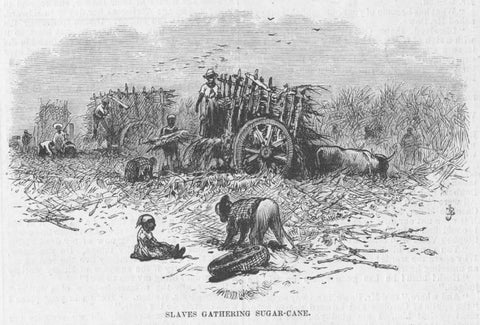

Some countries had not yet abolished slavery and used coolies simultaneously with Black slaves to enhance their workforce. For example, Cuba did not abolish slavery until 1886 (Yun & Laremont, 2001). Cuba’s economy relied heavily on its sugar plantations, which functioned efficiently thanks to cheap labor (Gines-Blase, 2021). At the time of the coolie trade, Spain had colonized Cuba and it was politically and economically unstable, which meant coolie labor was a much-needed infusion of cheap labor (Gines-Blase, 2021).Coolies bound for Cuba arrived at a port in Havana and were transported 83 kilometers (51.5 miles) away to the sugar plantations of Matanzas (Yun & Laremont, 2001).

China

China had been experiencing unrest, rebellion and war, so it was initially appealing to the impoverished men of the Guandong province to accept an offer of free emigration in exchange for signing a coolie contract (Yun & Laremont, 2001). Over 35 years, about 1,000,000 Chinese people, largely men, were trafficked, with approximately 142,000 of them sent to Cuba as part of the coolie trade (Yun & Laremont, 2001).

At the time of the coolie trade, Macao was under Portugese rule. It became an extremely popular port for exporting coolies from China to Cuba. This is because, in 1858, the British stopped sending coolies to Cuba and disallowed Spanish ships from entering Chinese ship ports. The British had recognized that by providing cheap coolie labor in Cuba, they were allowing the Spanish to overtake them in the “world sugar economy” (Yun & Laremont, 2001, p. 112). In response to the actions of the British, Spain began smuggling Chinese coolies out through the Macao (under Portugese rule until 1999) and the Philippines (under Spanish rule until 1898). By 1859 nearly every coolie ship departed Macao.

In 1865, as an act of political retribution, Britain publicly derided Spanish coolie trafficking, yet they continued transporting coolies to their own colonies (Yun & Laremont, 2001). [Not-So-Fun Fact: The British simultaneously became the most dominant coolie traffickers as they were working publicly to abolish African slavery. The British embargo on trans-Atlantic transport of African people for the purpose of slavery meant that places like Cuba had to find more discreet methods of importing African slaves and purchasing a slave became more expensive. Cuban people needed cheaper labor so they could price their sugar competitively].

Transport

Coolies were transported from China on ships, many of which had formerly been used as African slave ships (Yun & Laremont, 2001). The coolie ships often had slave names (eg Africano, Mauritius) or ironic names (Dreams, Hope, Live Yankees, Wandering Jew) (Yun & Laremont, 2001, p. 110). Many did not survive the journey, with “approximately 16,400 Chinese coolies [dying] on European and American coolie ships to Cuba during a 26-year period” (Yun & Laremont, 2001, p. 111-112). This accounted for a mortality rate of 12-30%, though, on some voyages, the death rate reached 50% (as in the case of the Portuguese ship Cors in its 1857 sailing). These deaths were caused by violence, rebellions,thirst, suffocation and sickness (Yun & Laremont, 2001).

On Arrival

When coolies arrived in Havana, Cuba, they were locked in depositos (temporary holding) until their contracts were auctioned off in lots in the same market used to sell slaves (Hu-Dehard, 1993).

Life and Work

Once a man’s contract was auctioned to a plantation owner, the coolie moved to the plantation, where he lived and worked. Coolies lived in the same locations as current and former plantation slaves.

They were treated in the same way as slaves, controlled and punished with “stocks and metal bars [cepo and barras], leg chains [grillete], whippings [azotes], jails and lockups, even executions” (Hu-Dehart, 1993, p.76).

WHEN

A timeline of the Chinese coolie trade and the political and social response to the trade, with a focus on the Macao-Havana ports follows:

1600s: Jan Pieterzoon Coen of the Dutch East Indies introduces the idea of Chinese men as global laborers. He believed that Chinese people are the best workers in the world and, therefore, should be taken captive and forced to work under his leadership (Yun & Laremont, 2001).

1791: Blacks in Cuba outnumber whites, due to the import of many African slaves (Clancy, 2009). This makes the Cuban sugar plantation owners and non-Black Cubans anxious.

1805:

- The Hatian Revolution concludes following a revolt of the Black slaves.

- Cuba becomes the world’s dominant sugar producer. Non-Black Cubans and Cuban slave owners grow concerned about the possibility of a slave rebellion.

- Due to Cuba’s booming sugar industry, plantation owners require additional laborers to work the sugar plantations. (Yun & Laremont, 2001).

1814: The Treaty of Ghent is signed, whereby the United States and Britain commit to abolishing African slave trade.

1830s: Britain begins transporting Chinese and Indian coolies to British colonies such as Trinidad and Guyana. They become the dominant coolie traffickers.

1842:

- The Webster-Ashburton Treaty is signed. Great Britain and the United States begin to monitor the west coast of Africa to ensure there is no more slave trade through European nations to their colonies. Suddenly, the Americans and British need another source of inexpensive labor for their colonies.

- China loses the first Opium War (1840-1842) Britain now occupies five of its major ports, which Britain uses to run the coolie trade.

1856: Peru prohibits importation of Chinese, but coolie importation kept going, just at a slower pace (Farley, 1968)

1858:

- Recognizing that sending cheap coolie labor to Cuba was helping the Spanish colony overtake them in sugar production, Britain stops sending Chinese coolies to Cuba and forbids Spanish ships from entering Chinese ports.

- The Spanish pivot and began smuggling coolies out through Macao, which was under Portugese rule.

1859:

- Macao becomes the most active port for coolie ship departures.

- China loses the second Opium War (1857-1859), leading to the takeover of a total of 12 of its major ports by Britain, France and the United States.

1860: Convention of Peking: Peking permits the “emigration of Chinese laborers and their families in British vessels”. Britain forbids the trading of Chinese coolies, but Spain and Portugal do not.

1862: In response to anti-coolie political sentiment, Abraham Lincoln [link to Lincoln content] signs an Anti-Coolie bill, which forbids American-owned ships from transporting coolies.

1865: The British government denounces the Spanish coolie trade on the global stage. In the background, they continue trafficking coolies to their own colonies (Yun & Laremont, 2001).

1874: After receiving a report titled “The Cuba Commission Report”, accompanied by over a thousand supporting depositions describing the ways in which Chinese men were forced to sail to Cuba and the horrific circumstances they endured on arrival, the coolie trade is officially ended by the Chinese government, yet those coolies still under contract in Cuba were required to complete them (Yun & Laremont, 2001, p. 100; Hu-Dehart, 1993).

WHY

Why Trade in Coolies?

The answer is primarily money. Everyone but the coolies themselves stood to gain financially from the trade.

Plantation owners paid traffickers $400 to $1,000 for each coolie contract (Farley, 1968).

The cost to acquire a Chinese coolie was less than half the cost to purchase an African slave in the 1840s and 1850s. So, while Africans were still being traded on the down low, coolies were a more cost-effective labor source for Cuban plantation owners (Yun & Laremont, 2001). Once a coolie’s contract was purchased by a plantation owner, the owners bought, sold and traded their coolies like slaves. The contracts the coolies signed entitled them to a pay of four pesos per month. They then lost part of their tiny salary to deductions the plantation owner took for their room, board, and even for their travel from China. These ‘expenses’ were so high that even after eight years of indentured service, a coolie would owe money to their boss/master/owner. That is, unless their boss renewed their contract without their consent, thus forcing them to continue their servitude indefinitely (Yun & Laremont, 2001).

On the backs of the coolies, Cuba became the world’s premier sugar producer: “In 1830, Cuba produced 105,000 tons of sugar. Forty years later, Cuba produced almost seven times more or 703,000 tons of sugar while its closest competitors produced approximately 100,000 tons…” (Yun & Laremont, 2001, p. 105).

Another reason for importing Chinese coolies to the workforce was political, as opposed to economic. Cuban plantation owners became uncomfortable with the large Black population in Cuba, which was due to the importation of African slaves. In 1791, Blacks began to outnumber whites in Cuba. For example, in 1841, Cuba's population was 50% Black, with 589,333 Blacks - a combination of slaves and free men, and only 418,211 whites.This inspired the Spanish government to follow in Britain’s footsteps and import Chinese coolies to Cuba (Clancy, 2009).

HOW

How were coolies recruited?

How did the coolies experience ship life on route to their destination?

How did the coolies survive?

How did the coolie trade come to an end?

How Were Coolies Recruited

Chinese men were recruited through lies and false promises of trouble-free emigration, or by force (Gines-Blase, 2021; Hu-Dehart, 1993; Yun & Laremont, 2001). These men were the lowest class of citizen, often uneducated and illiterate. They were told the journey overseas would take two weeks, when the journey was actually longer than three months (STSC 077, 2015).

Examples of tactics used to ensure Chinese men would board the ships include:

- Being encouraged to sign contracts and board the ships by their friends who were paid by traffickers (Yun & Laremont, 2001)

- Being deceived with promises of good wages and working conditions (Gines-Blase, 2021)

- Being made to board the ship in order to repay a debt (Gines-Blase, 2021)

- Being tortured until they agreed (Gines-Blase, 2021)

- Being recruited by crimps, fellow Chinese men who worked for the Western traffickers (Hu-Dehart, 1993).

Once the men agreed to sign a contract, they were held in locked and guarded stations until it was time to sail (Gines-Blase, 2021).

How Did Coolies Experience Ship Life?

Coolie ships were referred to as “floating coffins” or “devil ships” due to the high mortality rate of the men who set sail (Hu-Dehart, 1993, p. 75; Yun & Laremont, 2001, p. 111-112). Reports indicate that mortality rates on the coolie ships ranged from 12 to 30 percent, with approximately 16,400 men dying on ships destined for Cuba during the time of the coolie trade (Yun & Laremont, 2001). This reflects a death rate for coolies sent to Cuba of approximately 16 percent (Hu-Dehart, 1993). Deaths occurred for many reasons, including violence brought on by rebelling coolies, suicide, illness and neglect (thirst, starvation) (Hu-Dehart, 1993; Yun & Laremont, 2001). Coolies who petitioned to disembark were denied and the poor conditions on board the coolie ships were covered up (Gines-Blase, 2021).

Despite the horrific conditions in which the coolies found themselves, they were known to have been quite clean, “fond of dabbling in water…[wearing] around their necks pieces of muslin to use as towels. Many had tooth-brushes and little pieces of bone for scraping the tongue” (Holden, 1864, p. 5). The coolies were fed twice per day, mainly rice, salt fish and tea.

For entertainment, the coolies spent time gambling with dominoes, arguing, playing musical instruments and even putting on theatrical performances (Holden, 1864, p. 5).

How Did Coolies Respond to Their Indentured Labor Experiences?

Coolies responded to their exploitation and victimization in a similar manner to the African slaves who worked on the plantations before them: they rebelled wherever possible (Hu-Dehart, 1993). They rebelled by protesting to authorities, escaping, committing suicide, and some joined “insurrections against Spain in Cuba's Ten Year War in order to bargain for their personal freedom” (Hu-Dehart, 1993, p. 76). Unfortunately, the coolies hit dead ends when protesting to government officials due to the sway the plantation owners held over the judicial system (Hu-Dehart, 1993).

How Did the Coolie Trade End?

For many years there was varying public outcry about the coolie trade. In 1874, China finally put an end to the coolie trade “after a multinational commission, led by Chen Lanbin, travelled to Cuba and issued a disturbing report on the mistreatment of Chinese workers” (Gines-Blase, 202, p. 3-4).

References

Clancy, C. (2009). The linguistic legacy of Spanish and Portuguese : colonial expansion and language change. Cambridge University Press.

Dorsey. (2004). Identity, Rebellion, and Social Justice among Chinese Contract Workers in Nineteenth-Century Cuba. Latin American Perspectives, 31(3), 18–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X04264492

Farley, M. F. (1968). The Chinese Coolie Trade 1845-1875. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 3(3), 257. https://ezproxy.library.yorku.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/chinese-coolie-trade-1845-1875/docview/1303205783/se-2

Ginés-Blasi. (2021). Exploiting Chinese labor Emigration in Treaty Ports: The Role of Spanish Consulates in the “Coolie Trade.” International Review of Social History, 66(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020859020000334

Holden, E. (1864, June). A CHAPTER ON THE COOLIE TRADE. Harper’s New Magazine, XXIX(CLXIX), 1-10.

Hu-Dehart. (1993). Chinese coolie labor in Cuba in the nineteenth century: Free labor or neo-slavery? Slavery & Abolition, 14(1), 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/01440399308575084

Jackson, W.H. (n.d.). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coolies_boarding_ship_LCCN2004707914.tif

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. (1880 - 1905). Coolies embarking at Macao Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-37a2-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. (1896). Coolie recruiting office Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/110dae90-2c5a-0135-421b-01dd6c61d3df

Meagher, A. J. (1975). The Introduction Of Chinese Laborers To Latin America: The "coolie Trade," 1847-1874 (Order No. 7601797). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (302752113). https://ezproxy.library.yorku.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/introduction-chinese-laborers-latin-america/docview/302752113/se-2

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. (1859). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Negro_dance_on_a_Cuban_plantation_Coolies_and_Negroes_;_Farm_scene_near_Havana._LCCN2017658722.tif

Narvaez. (2010). Chinese coolies in Cuba and Peru: Race, labor, and immigration, 1839-1886. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

The New York Public Library. Coolie trade on ship Norway, 1857 Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-1d44-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

The New York Public Library. (1864). Barracoons at Macao Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-404a-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Pelcoq, J. (n.d.). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Le_Tour_du_monde-02-p356.jpg

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. (1874-12-26). Slaves gathering sugar-cane Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-e55e-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Staff of the Illustrated Times, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. (1860). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Garden_of_planter%27s_residence_-_Illustrated_Times_1860.jpg

STSC 077. (2015). Mutiny! Violence and Resistance Aboard “Coolie Ships”: Fall 2015 First Year Seminar, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved from https://scalar.usc.edu/works/the-voyages-of-the-clarence/index-4

Thomson, J. (n.d.). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MACAO.jpg

Thomson, J. (before 1898). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chinese_coolies_carry_their_burdens.jpg

Thomson, J. (1871-1872). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CHINESE_COOLIES.jpg

Tropenmuseum, part of the National Museum of World Cultures, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Unknown (n.d.), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Enslaved_Chinese_coolie_in_Peru_1881.jpg

Yun, L. & Laremont, R. R. (2001). Chinese Coolies and African Slaves in Cuba, 1847-74. Journal of Asian American Studies, 4(2), 99–122. https://doi.org/10.1353/jaas.2001.0022

Share this post

- Tags: china cuba